From a provincial capital to a modern metropolis, how 1908 Musi floods changed Hyderabad

By Yunus Y. Lasania

Hyderabad: Rainfall is typically measured in millimeters (mm), and showers of about 100 mm (3.93 inches) are considered to be heavy rains now in Hyderabad. But in 1908, the recorded rains on 28 and 29 September at Shamshabad, one of the principal rain-gauge stations in the catchment area of the river, was 12.8 inches in 24 hours and a staggering 18.90 inches in 48 hours, resulting in the worst floods that the city has ever witnessed in its recorded history.

The 1908 Musi river floods are remembered as a calamity today, and it is etched into Hyderabad’s history books forever. But it is more than just a historic event, as it also changed the very course of the city’s history and its landscape. The floods destroyed the city in entirety, but it also made the administration rethink its priorities.

Hyderabad was eventually made flood-proof and was also turned into a modern metropolis in the first half of the 20th century as a result. Never were such devastating downpours witnessed. Not only did it lead to a total collapse of the infrastructure in many parts of the city, it is said that the situation was so bad that Mahbub Ali Pasha, the reigning sixth Nizam (of the Hyderabad state) in 1908, himself went around the city in his car to help people.

But more than anything else, it changed two things: Hyderabad’s core public infrastructure, and the medical facilities of the city, which were completely overhauled and modernized by Osman Ali Khan, Mahbub Ali Pasha’s son and the last Nizam. The city, which was also hit by the plague after 1911, was rapidly developed, with modern institutions like the High Court, Osmania General Hospital, Kachiguda railway station, etc. apart from spacious housing, and modern markets for the public.

It is in that context today that we need to relook at how a provincial government, run by a monarch more than a century ago, changed Hyderabad, especially with regard to public healthcare. We also need to understand that heritage structures like the Unani Hospital, OGH, the High Court, etc., are not just old beautiful buildings with architectural value, but that those are remnants of the city’s transformation from a provincial capital into a modern metropolis.

A re-look at our city’s past, especially in the context of a pathetic situation that Osmania General Hospital (which has now been sealed shut) is in today, might help us understand things better.

Chloroform Commission:

It also equally important to understand that Hyderabad’s development, to a certain extent in the medical field, in fact, had begun much before the 1908 Musi river floods. Under Mahbub Ali Pasha, in 1888, the Chloroform Commission was set-up to study the usage of chloroform as anesthesia while treating patients. Two commissions had been set-up, to examine the dangers of using the chemical then.

The first commission, which was appointed in 1888, was applied for by Surgeon-Major E. Lawrie, Residency Surgeon, Hyderabad, who wanted to show by experiments upon dogs that in death from chloroform “the respiration always stops before the heart”. This point having been proved, the second Commission was applied for to experiment further.

In a report prepared on the work of the first Commission, the experiments led its members to conclude that “that chloroform may be given to dogs by inhalation with perfect safety, and without any fear of accidental death, if only the respiration, and nothing but the respiration, is carefully attended to throughout.” It was one of the most important medical experiments of its time, which was in fact carried out at the state-run Afzal Gunj hospital which would later get damaged in the 1908 floods, and over which Osmania General Hospital would be built eventually.

The floods and Sir Visweswaraya:

Hyderabad’s history is replete with the Musi river (called so due to its two streams Musi and Esi) flooding the city on more than one occasion. The earliest recorded instance is in 1631 and later in 1678, during the reign of Abdullah Qutb Shah, the 6th Golconda ruler. The next one came in 1687 while his successor Abul Hassan was fighting Mughal emperor Aurangzeb's army during the final war with the Delhi sultanate.

Aurangzeb's army, it is said, suffered great damage in 1687 when sudden rains in summer caused floods during the 8-month long siege of Hyderabad. In total, 14 major floods are believed to have hit Hyderabad in the past, with the last one being in 1908, which damaged about 59000+ houses, washed away bridges and killed thousands of people.

One of the main reasons behind the massive destruction was that several water tanks or beds abounded on both the northern and southern banks (on which the Old City exists) of the Musi river. According to the legendary engineer M. Visweswaraya’s autobiography, there were 788 tanks in a basin of 860 square miles of the Musi River, roughly at the rate of one tank for every square mile of the catchment.

Residency Gate in flood (1908) / Source: Siasat Archives

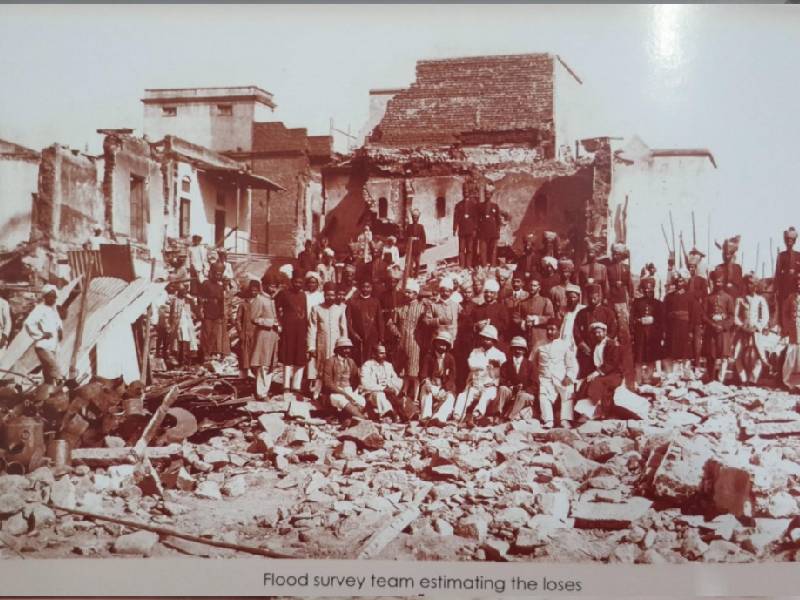

Flood survey team estimating the loses / Source: Siasat Archives

Of the total tanks, 221 were breached, which resulted in the catastrophic floods. Archival images from September 1908 show harrowing pictures of a broken Afzal Gunj bridge, damaged homes, and a flooded British Residency (now Koti Women’s College) gate, among other things. The Afzal Gunj hospital, over which Osmania Hospital stands today, was also believed to be extensively wrecked during the floods.

But in calamity, the city would also have a chance to reinvent itself. The then Nizam (6th), Mahbub Ali Pasha, called for Visweswaraya, as he wanted an engineer to examine the damage and to suggest measures to essentially make the city flood-proof. Visveswaraya, who was traveling in Italy in 1908, would eventually join as a Special Consulting Engineer for the Hyderabad state’s government on April 15, 1909.

Flood-proofing Hyderabad with Osman Sagar (Gandipet) and Himayat Sagar:

The legendary engineer, after carefully carrying out extensive surveys pointed out that the damaging floods occurred because many water tanks in the city had been breached. Visweswaraya surmised that for Hyderabad to be immune from the Musi River’s historic wrath, storage reservoirs of adequate capacity had to be built for “temporarily impounding all floods in excess of what the river channel could carry”.

Those two reservoir dams that he proposed were eventually called Osman Sagar (known a Gandipet lake) and Himayat Sagar, which today have a full-tank capacity of 45 million gallons per day (MGD). Hyderabad’s daily water supply today is about 462 MGD, of which only about 15 MGD is now drawn from both the historic lakes.

Osman Sagar/ Source: Siasat Archives

Both the reservoirs were built during the time of Mir Osman Ali Khan, the last Nizam (1911-48), as his predecessor had died in 1911 itself, much before any developmental work could take place.

It should also be remembered that the Qutb-Shahi era Hussain Sagar (built between 1560 and 80) was still a drinking water lake as well. The foundation of Osman Sagar was laid in on 24 March 1913 (source: M. Visveswaraya autobiography), while the Himayat Sagar was built some years later. The Musi River is called so as two of its streams, Musa and Esi, converge at the Tipu Khan Bridge near the historic Golconda Fort.

Like that, the Musi River was finally tamed, and Hyderabad was never flooded again. It may also be noted that Visveswaraya, who left Hyderabad in November 1909, was once again brought back in 1922 to design a new and modern sewerage system (he had given a plan earlier, but it was not carried out), as the Musi river used to also turn into a huge sewer, especially in hot weather (it has now become a perpetual sewer in Hyderabad)

“When the improvements suggested were carried out and the city was equipped with clean houses, flush-down lavatories, dustless roads, paved footpaths and a plentiful supply of open spaces, parks, and gardens, it was thought Hyderabad would be able to hold her bead high among her sister cities in India,” wrote Viswesvaraya, in ‘Memoirs of My Working Life’, his autobiography.

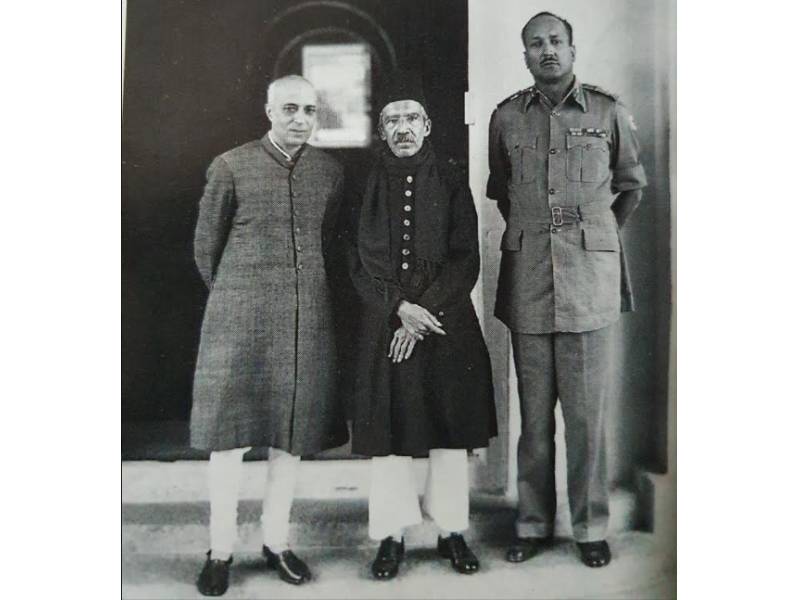

Former Prime Minister Pundit Jawaharlal Nehru (left), Osman Ali Khan and

J. N. Chaudhri, former military governor of the erstwhile Hyderabad state (post annexation to India)

City Improvement Board: Hyderabad’s ticket to transformation

The year 1911 was when Osman Ali Khan ascended the throne, and became the seventh and last Nizam of the erstwhile state of Hyderabad. His accession, unfortunately, would also be marked with an epidemic, as cases of the bubonic plague was beginning to surface in Hyderabad, which alerted the city’s administration.

Luckily for the city, the Nizam’s government rose up to the occasion, and changed the very contours of Hyderabad itself in the process, perhaps in a fundamental way since the city’s very foundation (Charminar) was laid 429 years ago in 1591. The birth of the City Improvement Board (CIB), constituted by Osman Ali Khan to develop Hyderabad, in 1912, may even have lessons for our current government on how to deal with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

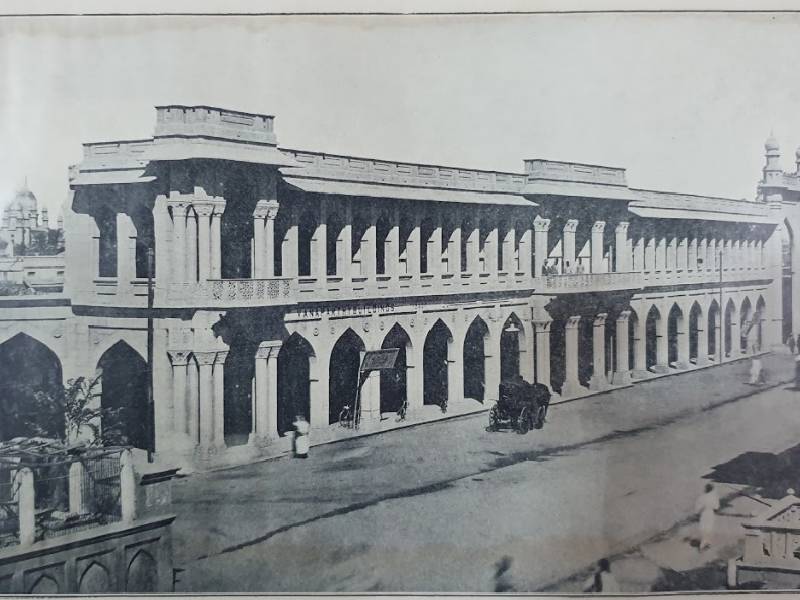

View of Pathergutty with Arcade/ Source: Yunus Y. Lasania

That is because apart from constructing major public infrastructure buildings like the High Court, Govt. City College, Osmania General Hospital, Unani Hospital, etc., the CIB also drew redevelopment plans across to decongest slums across the city. Not only did the then government concentrate on public infrastructure, but it also thought about the poor, for whom sanitary houses were built and given on rent.

While it may be noted the erstwhile state of Hyderabad (which had 16 districts; 8 in Telangana, 5 in Maharashtra and 3 in Karnataka) generated most of its revenues from farming taxes and levies, there is also no doubt that the Nizam can also be credited with developing Hyderabad. The same however can’t be said about the rural areas, which in fact were quite backward, especially Telangana.

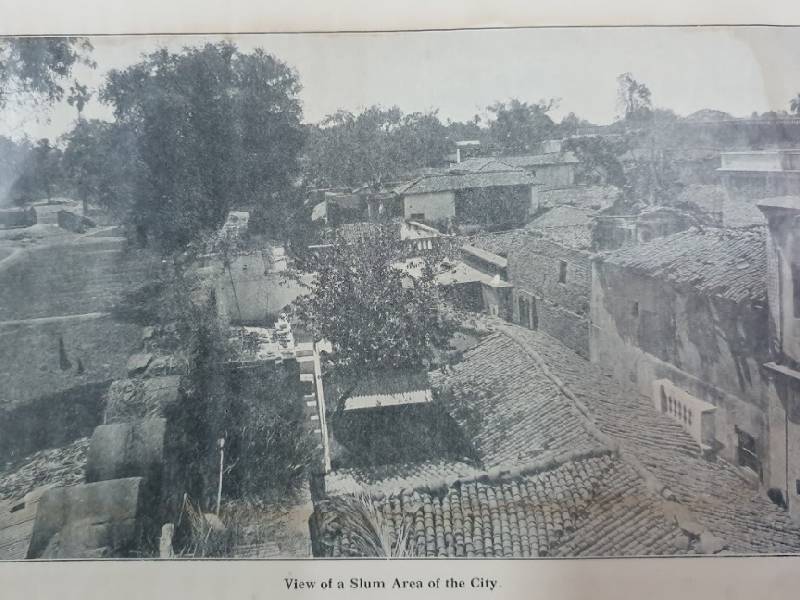

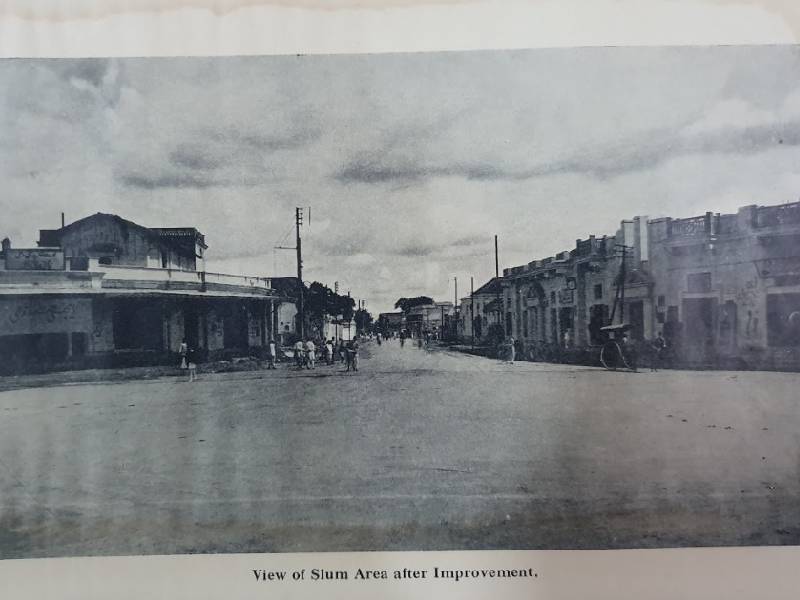

View of slum area before and after improvement/ Source: Yunus Y. Lasania

After the CIB came into being, about Rs.30 lakh was spent in building 2,500 houses in 12 localities. The homes, which were classified under A, B, C, and D classes (with each differing in size and amenities) Keeping sanitation and hygiene in mind, the newly-constructed homes, which were to be given to occupants on a hire-purchase system spread over 15 years, were designed with toilets, verandas and kitchens.

The before-and-after pictures of slum areas that were redesigned under the CIB particularly are striking, as the changes show what the government can do it if it really wants to improve infrastructure. Out of the total, Rs.50, 85,200 that was spent to develop the city, Rs.14, 36,565 was used for slum clearance, constructing and improving traffic roads, constructing drains, and other miscellaneous works.

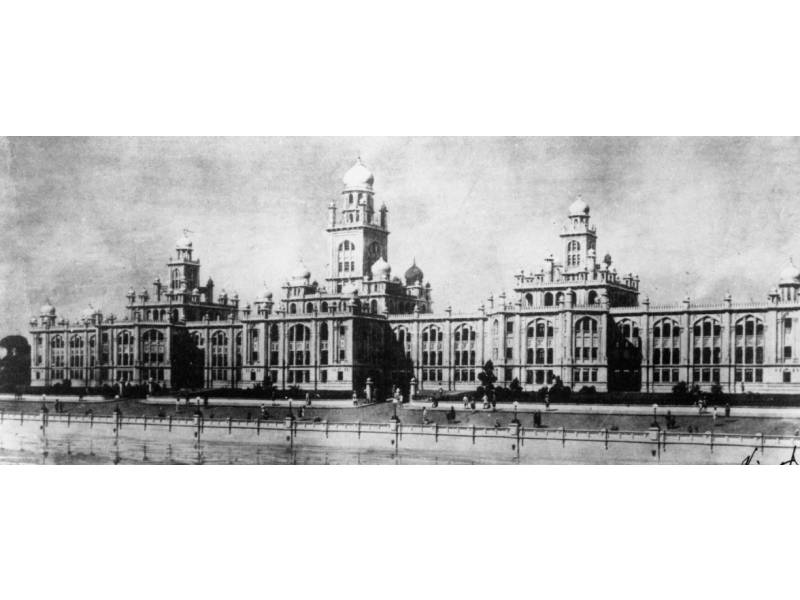

Osmania General Hospital, scripting medical history:

Osmania General Hospital (OGH), along with the High Court and Govt. City College today is a part of the skyline when one looks across the Musi River. All three of those heritage structures (and others like the Kachiguda railway station were designed by the architect Vincent Esh who also designed the Victoria Memorial in Kolkata) and built around the same time. Not to forget the creation of Osmania University in 1917, which was another landmark institution that was built.

OGH was completed in 1925 (it began operations in or around 1917), and is Hyderabad’s first-ever modern allopathic public hospital. It is a testament to the development that the city witnessed in the first half of the 20th century, which equally concentrated on the general public. Alongside it was the Unani hospital (completed 1925), which is also still functional. The same however cannot be said about OGH, as it is currently sealed shut by the state government.

Archival image of Osmania General Hospital / Source: MIT Archives

Archival image of Osmania General Hospital / Source: MIT Archives

The fact that Hyderabad had a fully-functional public healthcare center about a century ago is something that the OGH building reminds us of. Orders for its closure were issued last month after rainwater entered the ground floor wards. However, that was a result of government neglect and a drain getting blocked, as, in spite of continuous rains over the past week, not a single drop of water entered the building.

Everything I have written points to one thing: that a government can do anything it wants to. If a city can be fully developed and modernized aesthetically in a monarchy, then it is ironic that a democratically elected one is struggling to even take care of basic amenities in an ongoing pandemic. Instead of saving our heritage, what we have been continuously witnessing is the destruction of our precious heritage and history.

This story has been published as part of the Internews Information Saves Lives: Rapid Response Fund project to NewsMeter.