Interview: Meet Sanjay Shuka whose new book explores lies, relationships, dishonesty in society

Sanjay Shukla's two decades in journalism, content strategy and healthcare experience offers a voice that’s both knowing and disarmingly candid about Indian culture and views on dishonesty

By Anoushka Caroline Williams

Hyderabad: How to Lie Effectively and Get Away With It, Sanjay Shukla's book dwells into the psyche of Indian society

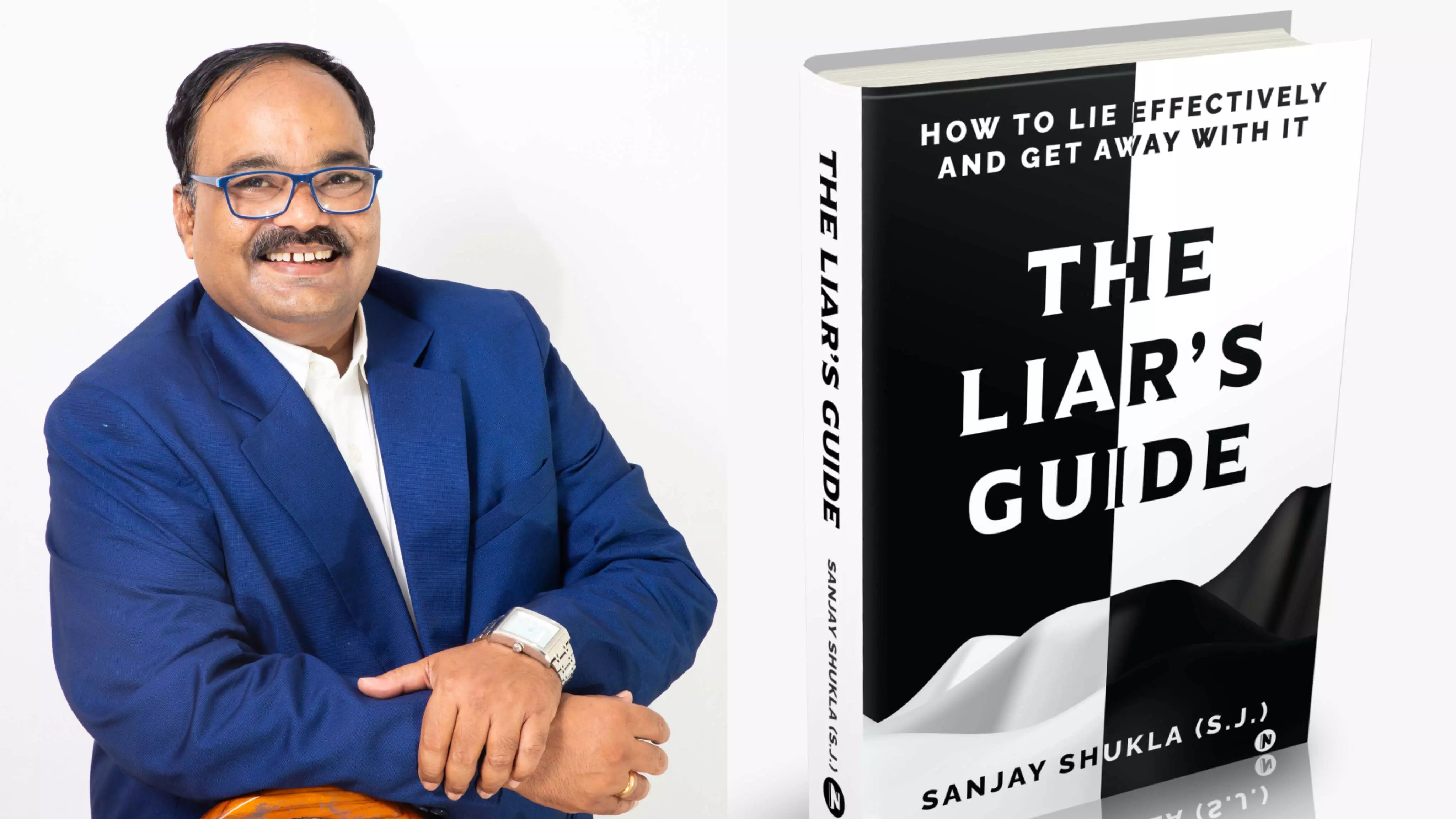

Hyderabad: What if lying wasn’t a moral failing but a social reflex—an essential skill to survive daily life in India? That’s the provocative idea at the heart of The Liar’s Guide: How to Lie Effectively and Get Away With It, a satirical debut by Hyderabad-based writer Sanjay Shukla, who goes by the pen name S.J.

Published by Notion Press, the book is a curious blend of self-help, social commentary, and tongue-in-cheek humour. Through eight chapters and five “golden rules,” it examines the lies we tell—polite, necessary, or strategic—and asks readers to reflect on their relationship with the truth. Drawing from over two decades in journalism, healthcare, and content strategy, Shukla uses his professional insight and cultural context to offer a voice that’s both knowing and disarmingly candid.

In this interview with NewsMeter, Shukla shares what led to the book, how Indian culture shapes our view of dishonesty, and why calling the book “the most honest thing he’s ever written” may itself be the biggest lie.

The Origins of a Lie

NM: What was the “aha” moment for this book?

Sanjay Shukla: It happened at an Irani café in Hyderabad—classic chai-sutta break. A friend claimed his uncle owned a palace in Bidar, then asked us to pay for his chai. Another, mid-egg puff, declared he was on a diet. We all laughed. That moment stayed with me. It made me realise we all lie every day—casually, instinctively—and rarely stop to examine it.

NM: You call this your most honest work. True or clever irony?

Sanjay Shukla: Let’s say… honestly, a lie, secretly the truth. The book being about lying, calling it honest is its first joke. But yes, at its core, it’s a reflection of the kind of small dishonesty we all live with.

On the Book Itself

NM: How would you pitch the book to someone who believes they never lie?

Sanjay Shukla: I’d say: you’re exactly who this is for. It’s not a book that catches liars—it reflects what we hide from ourselves. If you’ve ever said, “I’m almost there,” while still in bed, this book will hit home.

NM: You straddle satire and self-help. How did you manage that balance?

Sanjay Shukla: Tone was everything. The themes are serious—morality, memory, and emotional cost. But I chose storytelling and humour as entry points. If the reader laughs and then thinks, I’ve done my job.

NM: If you had to distil one essential “survival” lie, what would it be?

Sanjay Shukla: “I understand.” You may not. You may disagree. But those two words can save friendships, marriages, even meetings. Sometimes, they’re the social glue.

Culture, Context, and Conditioning

NM: How does Indian society shape our relationship with lying?

Sanjay Shukla: We live in a culture layered with expectations—familial, social, communal. Lies often act as emotional shortcuts. “I’ll try to come” is less confrontational than “I won’t.” We see it not as deceit, but diplomacy.

NM: Is lying more of a “social lubricant” here than elsewhere?

Sanjay Shukla: Absolutely. Jugaad is a national ethos—creative problem-solving with a twist. Lying isn’t a moral crisis for us; it’s often just part of getting things done.

NM: What’s a cultural lie we all heard growing up?

Sanjay Shukla: “Beta, do this… It’s for your good.” It’s been used to shape everything from careers to marriages. It may come from love, but it’s often about control.

On Memory, Ethics, and Writing

NM: What did your research reveal about the impact of lying?

Sanjay Shukla: That repeated lies—especially internal ones—can change what we believe. We don’t just lie to others; we edit our memories. That fascinated me.

NM: Has writing the book changed how you lie?

Sanjay Shukla: It’s made me more mindful. I hesitate before saying “I’m fine” or “I’ll call you later.” I’ve also become a better listener—lies often hide in tone, not just in words.

NM: Was moving from corporate content to satire liberating or daunting?

Sanjay Shukla: Both. Corporate writing is about precision and clarity. Satire allowed ambiguity and play. It felt freeing, but also scary, because now my name was on the punchlines.

On Technology and Storytelling

NM: You use AI in your creative process. How do you see that evolving?

Sanjay Shukla: AI is a sharpener, not a substitute. It can help structure, fact-check, or reframe—but the emotional intelligence, humour, and contradiction behind stories will always be human.

NM: If “truth” were a patient, how would you diagnose it today?

Sanjay Shukla: Chronic fatigue. Overexposed, misused, and barely trusted anymore.

Just for Fun

NM: What’s the last white lie you told?

Sanjay Shukla: Told my wife I was working late. I was debriefing at a bar. It worked… until she found the bar bill in my pant pocket while doing laundry.

NM: Which public figure needs this book the most?

Sanjay Shukla: Any politician who says, “We value your feedback and will look into it.”

NM: What’s one truth society isn’t ready for?

Sanjay Shukla: That most lies aren’t evil. They’re our way of coping, belonging, or protecting someone. It’s not always about deception—it’s often about survival.

Looking Ahead

NM: Is there a sequel in the works?

Sanjay Shukla: Maybe The Honest Lie: How to Live with Your Truths After Surviving Your Lies. But yes, fiction is next—ironically, the biggest lie I’ll ever tell.

NM: What do you hope readers take away from this?

Sanjay Shukla: A little laughter, a little self-awareness. If it helps people forgive themselves for being human, that’s enough. It’s not a manual for dishonesty; it’s a mirror for honesty’s many forms.

Conclusion

Sanjay Shukla’s The Liar’s Guide doesn’t teach you how to con. It teaches you how to think about the little lies you use every day, and what they reveal about your values, fears, and culture. In a society obsessed with image and perception, Shukla’s honest look at dishonesty may be just the truth we need.