When GoI denied records of Constitution Assembly Debates

Austin explained the merits and value of our Constitution as the ‘corner stone of a Nation’, in his first book which came after 15 years of origin of the Constitution in 1950.

By M Sridhar

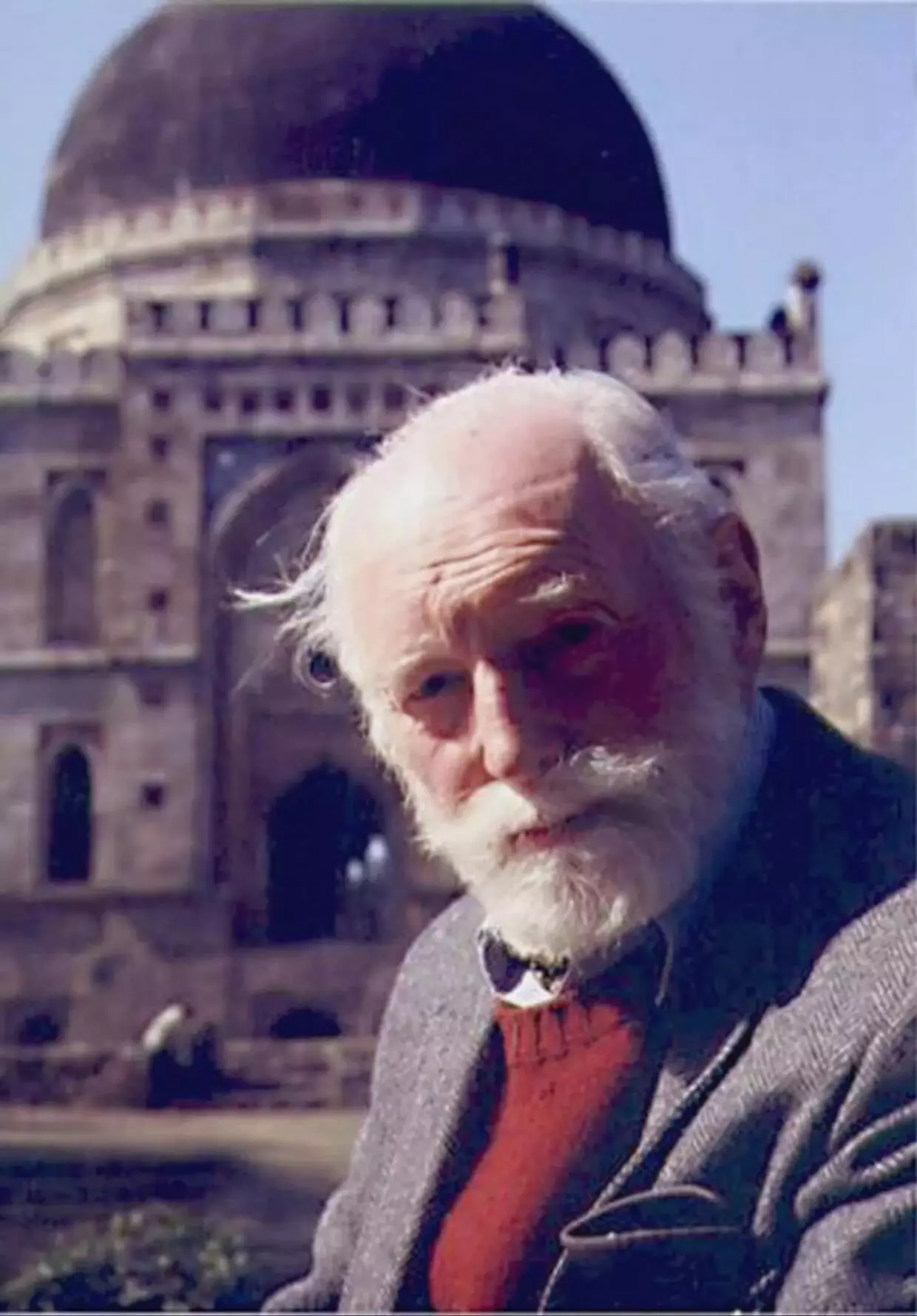

[Late Granville Austin, renowned writer of two great books on the Constitution of India, was with Late K Gupteswar, former Professor of Andhra University and this author. The first Principal of Pendekanti Law College, Hyderabad, Gupteswar organised a two-day seminar in 1997 in this college, on the eve of 50 years of Indian Independence, in which Granville explained the issues relating to working of the Indian Constitution. This author had the privilege to interview, share the dais along with Gupteswar and several of my colleagues. Granville Austin died on July 6, 2014]

It is surprising that a great Constitutional historian like Granville Austin (1927-2014) was initially denied access to certain vital documents, which were later provided by the initiative of none other than first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and later Law Minister Ram Jethmalani. If he was denied access to Constituent Assembly Debates and files of Law Ministry, his two great books — ‘Indian Constitution: Corner Stone of a Nation’ and

‘Working a Democratic Constitution: The Indian Experience’ — would have not come out. Austin explained the merits and value of our Constitution as the ‘corner stone of a Nation’, in his first book which came after 15 years of origin of the Constitution in 1950.

Best book on Indian Constitution

It was because of the openness of Nehru the first book of Austin (1966) gave us a vivid understanding of making of the Constitution. Nehru rightly gave him access to Constituent Assembly Debates and even to the private papers of Maulana Azad, KM Munshi and others. Austin’s research was systematic, meticulous and well founded on facts of each and every step in the Constitutional history from all possible angles.

This researching author in him was not satisfied with opinions expressed by the members in Constituent Assembly verbatim reported in the debates. He went to the members of Constituent Assembly personally and interviewed to know the background, circumstances, reasons and compulsions, if any, for the member to arrive at that opinion on vital aspects of Indian Constitution. In the process he documented the process of thought that emerged into an Article of the Constitution.

Earlier debate is documented but not the thought process. This book is much acclaimed as a scholarly analysis on the Indian constitution. Austin described Indian Constitution as, “first and foremost a social document,” one that embodied the objectives of a “social revolution.”

Professor of Law in Development at the University of Warwick, United Kingdom, Upendra Bakshi stated that Austin’s first book

“provides the most comprehensive, insightful and balanced account of the work of the Constituent

Assembly which drafted the Indian Constitution in the brief span of time from December, 1946 to

December, 1949 – a time of strife, turbulence and ferment not merely in India but in the entire world.”

The Economist reviewed this book saying: ‘The author has done for the Indian Constitution what CA Beard and other scholars have done for the Constitution of the United States. The author’s reading has been vast and he has undertaken much research in unpublished material… There is something majestic in the scale of the work that is appropriate to the subject matter.”

Second seminal work

For writing the second book (2000) Austin needed access to certain law ministry papers, which were denied. It was then Law Minister Ram Jethmalani who facilitated him access to files, which led to the highly authoritative book on working of the Indian Constitution. All the students of Constitution should thank both Nehru and Jethmalani, who in their capacity as holders of Constitutional office, helped provide access, otherwise the information would have been buried in those files without any use.

This book gives a ‘critical insight into four decades of the Indian Constitution and charts the course of constitutional reform in India from the euphoric idealism of the post-independence period, through the crisis-ridden years of emergency and up to Rajiv Gandhi’s brief stay in power’ (quoted from back cover of the book) and how the social, political and day-to-day realities of Indian people have been reflected in and directed the course of governance.

‘Working a Democratic Constitution: The Indian Experience’ will stand as the best lesson in research methodology and writing techniques for contemporary history writers. Austin met every living judge who contributed to 1,000-page judgment in Keshavananda Bharti case to understand the judicial process, which presented the origin of ‘basic structure’ doctrine of the Indian Constitution and its consolidation over a period of time.

This book takes readers to flashback of the dark days of Indian democracy — the Emergency in 70s, to the period that threatened secularism in 90s with acts like demolition of masjid, challenged the basic goal of equality with movements on reservations after Mandal recommendations and independence of judiciary. The author met senior advocates who argued before the apex court for and against Mrs Indira Gandhi on emergency amendments to find out reasons behind the contentions they took up including pressures, if any. The role of the press and judges during that period was critically analysed. After concluding research into the constitutional developments in India in 1986, he went on writing for more than a decade to produce the book in 2000. That was the seriousness. Each of the sentence was authenticated or established or attributed to an authority.

Former Attorney General of India, and member of the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague, Soli J Sorabjee wrote:

“This classical work of Granville Austin is a must for every judge, lawyer, historian, researcher, and other persons interested in the Constitutional history of India”. Judith Brown, Professor of Commonwealth History, Oxford University says:

“…this is no dry ‘constitutional history’. We are shown how examination of the issues and strains surrounding the constitution and its role in the Indian polity are a window into the nation’s public life, particularly in relation to democratic stability, national integrity, and the stated goals of socio-economic change…”

Fali S Nariman analysed:

‘With intimate knowledge gained by living in India for long periods, and talking to people who have seen it all happen the author unfolds the triumphs and strains of working a truly democratic Constitution’. Generally, books on Indian Constitution are heavily loaded with citations of court judgments. Austin takes the readers to the dynamics, power politics and deep-rooted social causes pertaining to burning issues, some of which also might have travelled to the apex court. It is not just judicial interpretation of provisions of Constitution, but their living impact on the life of a society that needs to be studied. The evolution of Constitutional law did not end with landmark commencement of Constitution on 26th January 1950, but it started to evolve, which was rightly evaluated by Granville Austin.

Granville Austin (1927-2014), a great name that comes to mind on the Indian Constitution, is no more (since 6th July 2014). He will be remembered for ever with vivid and effective documentation of the Indian constitutional history. We lost a living scholar exclusively dedicated to study and research the history of rule book of India. His writings have significantly influenced judicial process and evolution of Constitutional jurisprudence in India and beyond.