The flawed idea of three capitals

By Prof. Nageshwar K

Hyderabad: Y S Jagan Mohan Reddy's announcement that Andhra Pradesh may well have three capitals in the model of South Africa evoked massive political and public response across the state and elsewhere in Telugu-speaking areas around the world. Hinting at the possibility of Amaravati reduced to a mere legislative capital, Vishakhapatnam to be the executive capital and Kurnool as Judicial capital, the Chief Minister called this decentralisation suited to the tight fiscal regime prevailing in the state.

Jagan Mohan Reddy's aversion to Amravati is nothing new. As the opposition leader in the last house, he kept himself away from the foundation stone laying ceremony attended by the Prime Minister and Telangana Chief Minister. He vehemently opposed the land pooling for the capital which he called forcible land acquisition.

Jagan had nothing big to offer on Amaravati even in his election manifesto. The first budget saw a meagre allocation of Rs 500 crore for the capital. The budget speech was forthright in stating that the grandiose capital plan is no longer the priority. Adding insult to the injury, responsible leaders of the government went on making ambivalent statements on the future of Amaravati. The ultimate salvo came in the form of Chief Minister's own assertion that this government bids adieu to Chandrababu Naidu's grand capital dream.

The reasons given for justifying three distinct capitals are quite curious. Decentralisation essentially means devolution of administrative functions but not the relocation of State organs to three different places. The development opportunities certainly need to decentralise. Governance needs to be decentralised. Devolution of funds, functions and functionaries are a prerequisite for effective governance. But, locating the three organs of the State – executive, legislature and Judiciary – at three different places is now defined as decentralisation of development.

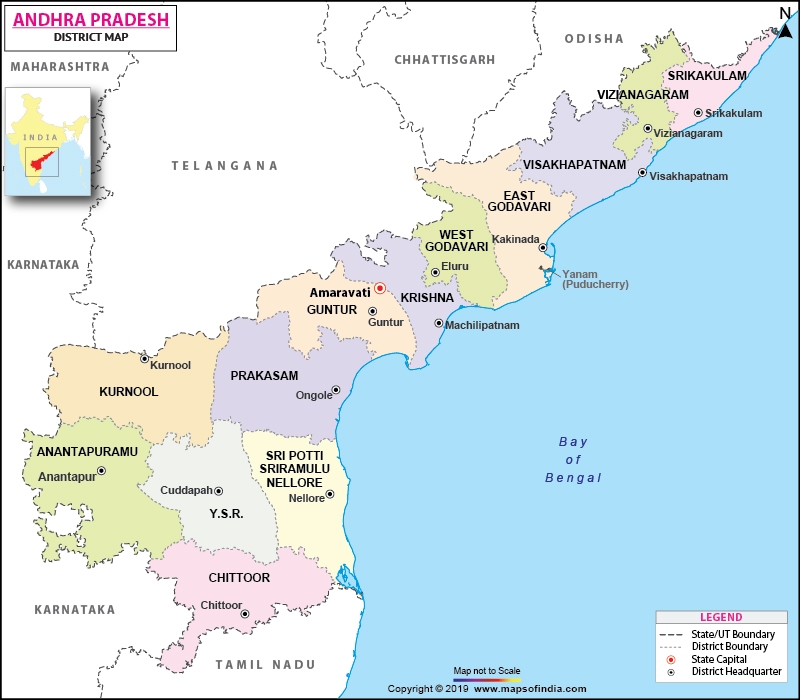

The distance between Amaravati and Visakhapatnam is 387 km, the distance between Kurnool and Amaravati is 310 km. Obviously the distance between Kurnool and Visakhapatnam is much higher at about 690 kilometres. Though technology bridges distance gaps in the modern era, the location of three wings of State at three different places separated by such long distances pose serious logistical challenges. The functions of the executive, legislature and Judiciary are inter-connected, though Constitutionally separate. The logistics shall impose additional social and economic costs on the already cash-starved State. Surprisingly, the argument for shelving grand Amaravati plan and adopting the three-capital plan is the fiscal stress the State is facing. But the alternative will certainly entail higher recurring expenses besides the dislocation of human resources it brings in.

Emulating the South African model for a state like Andhra Pradesh is simply irrelevant. Andhra Pradesh does not inherit the historical and cultural compulsions the Union of South Africa did due to its colonial and apartheid past. In fact, the then President Jacob Zuma in his 2016 State of the Union address urged the Parliament to consider doing away with multiple capitals and go for a single capital to reduce fiscal and logistical constraints.

In India's parliamentary democracy, the close relationship with which legislature and executive function need no special mention. The electorate hardly view their public representatives as legislators alone. The MLAs mediate between people and bureaucracy on any and every executive activity. In fact, several senior government officials attend court duties on any functioning day. Judiciary is loaded with cases that demand the government to respond. Thus, the three-capital plan not only entails fiscal wastage but puts severe stress on public representatives, government machinery and people at large. Inviting such complications is certainly undesirable though such a split capital plan may serve the parochial political demands.

YS Jagan quotes South African experience without making any analysis of its relevance to the Andhra Pradesh situation. In 1910, when the union of South Africa was formed, there was a dispute about the location of the capital city. The formula of executive, legislative and judicial capitals is the result of a compromise to distribute the balance of power throughout the nation. Pretoria had long been the home of foreign embassies and government departments. Cape Town was the seat of Parliament since the colonial days. Andhra Pradesh is not burdened by such historical legacy to emulate the South African model of three capital cities.

The global experience of choosing the capital is distinct to each country’s problems and situations. The capital of Nigeria was moved to the geographically central city of Abuja in 1991 to signify the unity of a nation divided along religious and geographic lines. Brazil shifted its capital from the crowded coastal city of Rio to inland city of Brasilia in 1961, aimed at bringing progress in the country’s hinterland. Similar such stories of historical, cultural factors defining the choice of capital city emanate from different countries. But Andhra Pradesh does not travel through such complex situations imposed by history to split its capital among three cities.

Just before the chief minister dropped a hint to this effect, the finance minister in an elaborate submission to the state Assembly made a compelling argument that the previous government’s choice of Amaravati was marked by insider trading, to the tune of over 4,000 acres, benefitting vested interests closer to former chief minister N Chandrababu Naidu and his alleged benamis. Notwithstanding the veracity of this allegation, a possible scam marking the formation of capital cannot be the valid reason for taking away the executive operations from Amravati. The government is well within its right to expose any such scandal and punish the guilty. It can even take over the land if something wrong is established. YS Jagan Mohan Reddy cannot tax the people of Andhra Pradesh for any omissions and commissions of his political adversary. The Municipal Administration minister has earlier stated that the capital city on the river bed of Krishna is prohibitive due to the condition of the soil there. Even the finance minister referred to this in his presentation to the Assembly. Such questions were raised even when the capital was contemplated here.

The earlier TDP government unilaterally brushed all these adverse opinions under the carpet to unveil its grand Amaravati plan. If this government feels the genuineness in the argument of environmental sustainability of the capital city on the river bed, it can make necessary modifications. Anyhow, the government is against any elaborate capital. A modest capital with administrative, legislative and judicial buildings will not be environmentally unsustainable and fiscally imprudent.

At least Rayalaseema has a justification in demanding High Court at Kurnool. As early as in 1937 an agreement was reached, popularly called Sribagh agreement between the leaders of coastal Andhra and Rayalaseema to locate either capital or at least the high Court in Kurnool. This Rayalaseema city was the capital of Andhra state between 1953 and 1956. Ideally speaking, three organs of the State – executive, legislature and judiciary – should be located at one place. But due to historical factors, one can appreciate relocating judiciary with which common man does not have a daily attachment. But splitting the executive and legislative functions of the capital between two different cities is not a prudent idea. Instead, the government should focus on distributing economic opportunities across North Andhra, South coastal Andhra and Rayalaseema.