Painting desert green: Satellite pics show transformation in Rajasthan

By Dheeshma Puzhakkal

Hyderabad: Desertification is fast eating into agricultural land across the globe. According to the United Nations, 135 million people could lose their livelihoods to deforestation by 2030. Land degradation has increased up to 90 percent in Indian states, says a report in DownToEarth.

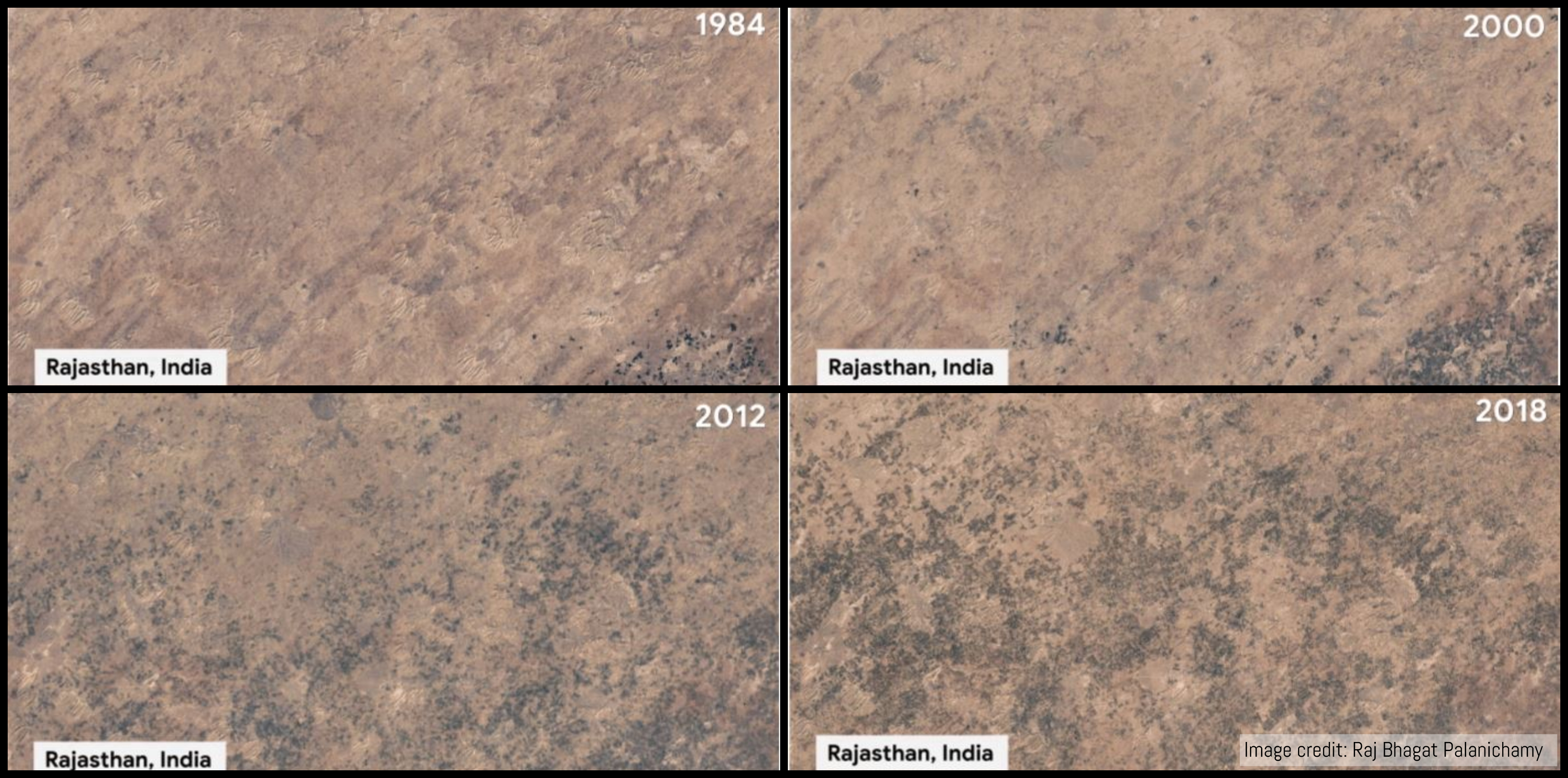

While the world is losing its green cover, satellite images show that Rajasthan has converted large belts of its desert into farmland in the last three decades.

In Rajasthan, the government has built a system of irrigation canals to prevent desertification near Thar and protect forest land. In the meantime, agriculture has taken over several waterless, desolate stretches across the state. This raises the question: is it possible for a desert to become an agriculture land?

Data of two decades captured by NASA satellites shows that China and India are the two leading countries in increasing greening on land. Though the public tends to attribute the increase in green to forest expansion, the satellite data reveals it is due to agriculture.

“82% of the greening seen in India – comes from intensive cultivation of food crops,” according to a NASA report.

Satellite images show that we have converted large swaths of deserts into farmland in #Rajasthan in the last 3 decades

Visualized using @googleearth! pic.twitter.com/GcZP2cXVPA

— Raj Bhagat Palanichamy (@rajbhagatt) December 28, 2019

For instance, the region shown in the satellite images is between Phalodi and Jodhpur. Even though there's a Phalodi lift project for bringing water from irrigation canals for nearby region, this section primarily depended on tube well for agriculture. Except for West Rajasthan that relies on canals, the rest of the state mostly depends on borewell for irrigation.

The cultivation pattern in Rajasthan is an attempt at changing a natural system and it's a big challenge, said Subha Rao, a former scientist at the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-arid Tropics (ICRISAT). "Our interventions are very minimal while nature forces are very strong. In the end, we will end up spending more money for a small product. So, is that worthwhile is what we need to talk about while launching such interventions." Rao said what one litre of water can produce in other areas will need five litres in Rajasthan.

He suggested that Rajasthan should have tried crops that suit its climate, meaning dryland crops. “Sustainability is a big question here. A long-time consequence of borewell farming in deserted areas depends on the depth of the borewell as well as in what rock formation they are in.”

(Satellite data credit: Raj Bhagat Palanichamy)